Human Milk: Programming Future Health

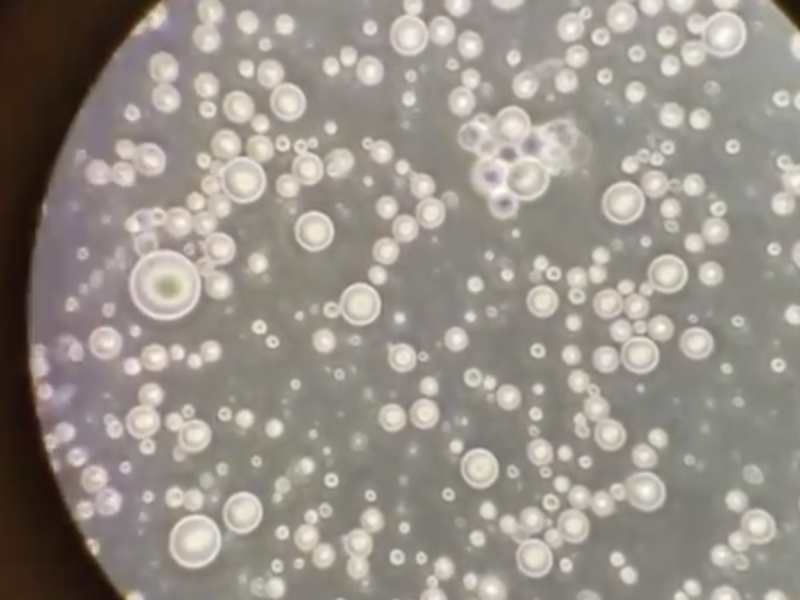

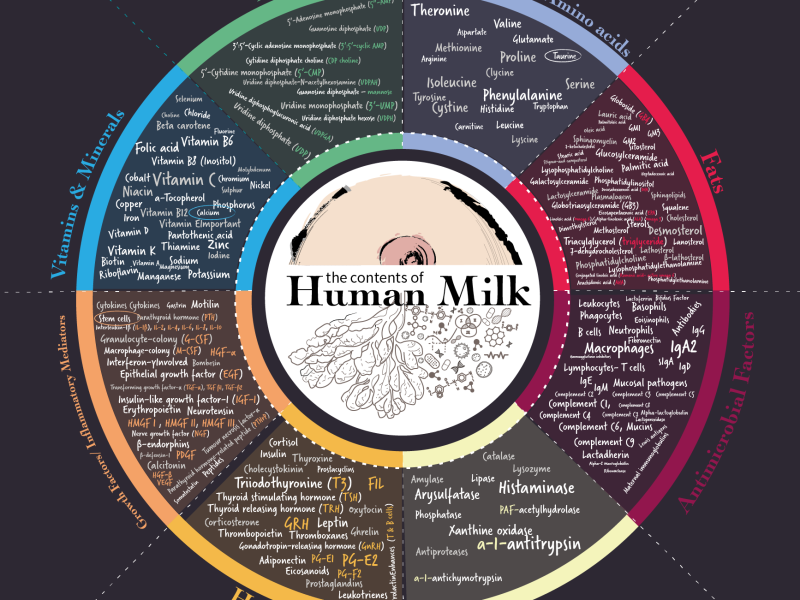

Human milk contains thousands of individual components working individually and synchronously, which have evolved to support the development of each unique human organ and tissue. Human milk has long been known to have specific impacts on the development and normal functioning of the brain, immune system, heart, and gut. But recent breakthroughs in the field of the microbiome, epigenetics and immunology has highlighted that human milk is essential for patterning long-term health and resilience against future infections and non-communicable diseases. Amongst the thousands of distinct bioactive molecules in human milk are components that kill cancerous cells, stem cells that may help infant organs respond to damage, scores of mechanisms that protect against infection, and natural painkillers. Much is still to be discovered.

The Microbiome

A normal diverse microbiome contains bacteria, fungi, viruses and bacteriophages that live in every organ in our bodies. One of the first microbiomes to develop is in the infant gut. Since its recent discovery, the gut microbiome has been shown to play vital roles in the normal development of the gut, brain and immune system. For example, the gut bacteria are ‘sampled’ by immune cells in the lining of the baby’s gut, which then use bacterial fragments to train the immune system to recognize helpful microorganisms from harmful ones. If the gut only receives human milk, this sampling process can go on for weeks or even months, giving all the newly developing immune cells chance to remember infectious threats for a lifetime.

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs)

Only humans have such a wide array of these ancient complex sugars. Over 200 different HMOs have been identified, and each mother produces a unique fingerprint that is related to her genetics and their environment. They can even vary according to the season. Twenty HMOs cannot be broken down for energy by the baby – they are produced by the mother to feed the Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus species of bacteria that form the basis of a healthy infant gut microbiome.

As well as helping the immune system and brain to develop, HMOs can trick harmful bacteria and viruses into binding to them rather than the gut wall, reducing the risk of gastrointestinal diseases. Very early stage research suggests the presence of some HMOs in milk are linked to a reduction in the risk of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), a fatal disorder that most often affects premature babies. This exciting avenue of research could support donor milk with specific HMOs to be targeted to the most vulnerable babies, while supporting their mothers to establish their own lactation.

A focus on lactoferrin

Lactoferrin is an ancient protein with an anti-bacterial and anti-viral effects that also inhibits the growth of cancerous cells. Laboratory tests have shown that lactoferrin inhibits infection by hepatitis B, hepatitis C, cytomegalovirus (Herpes family), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), adenovirus (one of the viruses that cause the common cold), poliovirus, enterovirus and others. It also helps babies to absorb their own iron stores, binding to the iron in their body. This removes free iron from the gut, which prevents it being used by harmful micro-organisms such as E. coli that need iron to survive.

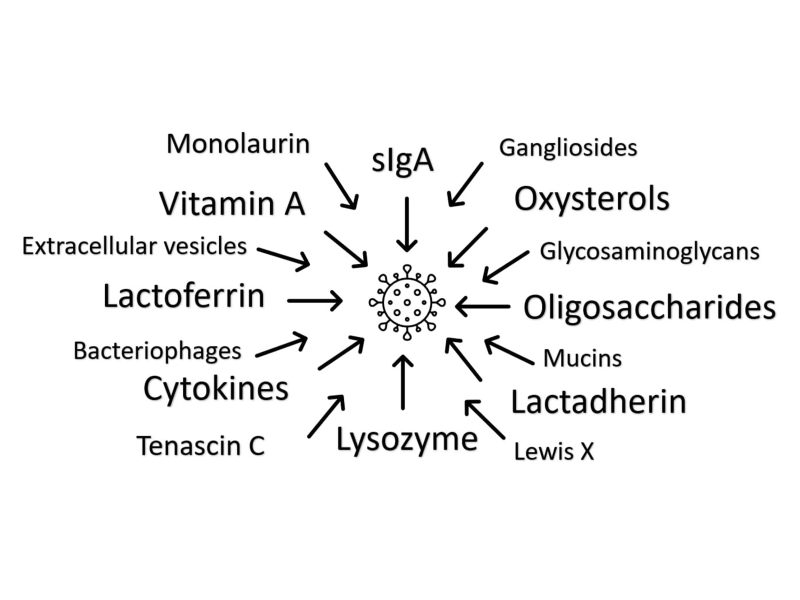

How does human milk destroy viruses?

A new review published in MDPI Microorganisms by Dr Natalie Shenker and Sophie Wedekind highlights 20 different ways that human milk acts against viruses, helping to support the baby’s immune system before they can fight viruses themselves. Excitingly, there has been very little research into most of these molecules, and there are bound to be even more as methods to study milk evolve. A whole field to explore and discover! Read the whole review here.

Research Grants from the HMF

Science underpins all of the work we do and is one of the HMF’s three core pillars. Our aim is to advance education and research in the field of health – in particular, the understanding of human milk. If you are a researcher and would be interested in applying for a grant from the Human Milk Foundation find out more here >